New England Ablaze: King Philips' War, 1675-1676

King Philips' War, fought from 1675-1676 in the region known as New England in the Northeastern United States, predominately in the states of Massachusetts and Rhode Island, was one of the most devastating and bloody wars in America's early colonial history. Named for the powerful and greatly revered chief Metacomet (b.1676), the conflict precipitated the virtual extinction of New England's greatly varied and long established Native American tribes in favor of the rapidly growing American colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, and the Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Two great figures dominate the military study of King Philips' War in New England, colonial officer and the "First American Ranger", Rhode Island born Captain Benjamin Church (b.1639-1718) of the Plymouth Colony, what is today South Shore and Cape Cod of the state of Massachusetts, and great

The son of sachem Massasoit, Metacomet was the paramount leader of the Wampanoag people who stretched throughout southern New England from Western Massachusetts into Connecticut, Rhode Island, and southern Massachusetts on the Atlantic Ocean. Metacomet ruled from Mount Hope Bay on the border of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Plymouth was apart of a loose confederation (United Colonies) of New England territories and colonies which included Massachusetts Bay Colony, Connecticut Colony, and the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, all of whom had banded together to protect New England territory after war broke out with the powerful Wampanoag Confederacy. The native tribes of New England before King Philips' War consisted of the Narragansetts in Rhode Island and parts of southern Connecticut, the Wampanoag of Massachusetts, the Pocumtucs in western Massachusetts, the Nipmuc in what is today mostly Worcester county (central Massachusetts), amongst several other smaller tribal bands. In Connecticut, the Pequot and Mohegan had assimilated following the Pequot War and were allied to the colonial government.

The Native populace of New England had suffered continually both due to the indirect and direct actions of the English colonists throughout the region from 1630-1675. Diseases brought by the large Pilgrim and Puritan emigrations to the Massachusetts colonies killed tens of thousands in less than a decade. Culturally their vast differences between the white men and the Native American tribes of New England were exacerbated out of indifference, ignorance, and at times pure malice and greed on the part of the New Englanders. The first major conflict between the two sides took place in 1636-1638 during the Pequot War.

Fought predominately in Rhode Island and Connecticut, this conflict saw the near complete eradication of the Pequots following the Mystic massacre of 1637 in which 400-700 Pequot men, women, and children were killed by a force of New England militia and Narragansett indians. Pequot resistance ended when their chief Sassacus who escaped the massacre was murdered by Mohawk indians and the last Pequot warriors in arms were defeated in Fairfield, Connecticut in the Great Swamp Fight of 1637. A year later the Treaty of Hartford ended inter Colonial-Indian warfare for nearly forty years.

Following the dreadful conclusion to the Pequot War, relations between the Native tribes and New Englanders did not improve. Native males were underemployed and slowly loosing their warrior identities in the lead-up to conflict; something King Philip and his more hawkish chieftains tried to exploit. Both hunting lands and agricultural lands were being lost continuously as the land approved for use by the tribes of New England shrunk further into the west and north. Many living in the immediate vicinity of New England towns and cities detested being subjected to the strict and utterly confusing Puritan law system which could fine and in some cases imprison them for endless trivial offenses.

New England natives could not legally own or purchase firearms until 1665-a "privilege" frequently taken away when the colonials became nervous about their "red skinned" neighbors intentions. All of these facts betrayed the relative trust and friendship between many New England colonials and Indians before King Philips' War began. In fact inter-European/Native trade was common and was indeed a staple of colonial economics during this period. Metacomet himself owned tribal and "English" lands in Massachusetts and enjoyed trading and hoarding a variety of finely made English goods including steel knifes, buttons, and cloth jackets.

The tide of war turned in the colonists favor following the Great Swamp Fight (or Great Swamp Massacre) of over 300 Narragansett at their winter lodgings in December 1675. Governor of the Plymouth colony and General of the United New England militia Josiah Winslow (b.1628-1680), led the New England army of around 1000 Englishmen and another 150-200 allied natives in person along with a slew of officers from all the colonies. Their target was the winter redoubt of sachem Canonchet in what is today South Kingstown, Rhode Island.

Canonchet had created a veritable refuge camp and colony in the middle of the frozen swamp. In this winter fort, 2,000-3,000 mostly women and children including 800-1,000 warriors kept bundled and hidden from the snowy and cold New England winter. The assault began on the morning of 19 December when Massachusetts men stormed across the frozen swamp and amazingly penetrated the large but lightly defended fort in their first attempt. Massachusetts militia captains Isaac Johnson, Davenport, and Joseph Gardiner were all slain by sharpshooters in the first assault, further Plymouth and Connecticut reinforcements were quickly shot down as well; most killed or mortally wounded in the snow where they fell. Many militia members froze or attempted to retreat when there officers had been mortally wounded or slain until Major Appleton of Massachusetts rallied them to continue the assault through the breach in the fort.

The Great Swamp Fight was to be the largest battle of the conflict and the most significant colonial victory as well. Benjamin Church was given permission by Governor Winslow to reconnoiter the fight for the fort with a handful of men. His rangers killed several Wampanoag outliers before charging into the fort to take part in the prodigious slaughter now ensuing from within. Warriors and non-combatants were being cut down and shot. Some women and children likely burned alive in their wigwams as dozens of warriors fled the fort. The cost of the battle was staggering for both sides; no less than 400 Wampanaog were killed and at least half that number were captured and executed later. The New Englander's lost 70 killed and 150 wounded of which 50 or more later died from their wounds.

For many months after the bitter defeat in the Great Swamp Fight, the war entered a steady cycle of insurgent warfare. Philip's warriors raided New England settlements in small parties or in larger groups of 20-40 warriors. In some cases a small band of three of four natives would attack a home, they might kill one or two colonists and then escape into the nearby forest or countryside to terrify the white man again. In other guerrilla attacks, horses or property were stolen. As the conflict dragged on, food became a scarcity and many native warriors were forced to steal provisions from farms and homesteads across the New England frontier. This type of guerrilla warfare continued whilst the United Colonies militias' searched for and killed "bad indians" in the hunt for Metacomet.

Metacomet met his end on 12 August 1676, assassinated near Mount Hope in what is today Bristol , Rhode Island

The regal chieftain's skull was placed on a pike in Plymouth where for over twenty years it stood until it turned bleached and began to crack. Alderman supposedly took one of the revered sachems hands as a war trophy; later preserving it in rum, he made a small amount of coin the rest of his life showing it to curiosity seekers at taverns and barrooms throughout the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies. Despite Metacomet's death the war would continue on until the final pitched battle was fought at Turner's Falls outside Springfield in May of 1676. In this battle the last remnants of Nipmuck warriors were finally defeated and driven from the northern reaches of the colony. In June the last organized band of Wampanaog natives was defeated and killed or captured outside of Marlborough, Massachusetts and thus King Philips' War came to an end.

Opposing Forces: Colonial Militia and Native Warfare, 1637-1675

Several units were what would be considered “elite”, known as "brisk blades"; such as Benjamin Church’s Rangers, a force of less than 200 Plymouth militia and Praying Indians. Though small in number, Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth infantry and cavalry companies were mostly well regarded, some were led by officers who were veterans of the English Civil War 1642-1651. The average militia unit from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth, Connecticut, or Rhode Island however was made up of men who did not know how to soldier and many who did not care to know how.

For many militia captains it was agonizingly laborious to get these men to march quickly, to get into battle formation, and to attack or retreat as a unit with a modicum of discipline and order. Armaments and weaponry were fairly standardized across most of the New England army. Smoothbore matchlock muskets were used by the average militia soldier. These were heavy and cumbersome .75 caliber "shoulder breakers" which were horribly inaccurate even at close ranges and which took nearly a minute to reload. Swords were commonly in use by the gentry and cavalry troopers. Pikes were also popular throughout the New England militia system during this period.

The native tribes of New England fought similarly across the frontier theaters of King Philips' War. The element of surprise was always paramount. The ambuscade and raid were prized above all methods of warfare though Metacomet's warriors fighting in large numbers were also highly effective against the untrained rabbles of New England militia. Long and short spears were used for medium ranged combat while bows and arrows and an increasing number of muskets were also used at long range by the Wampanoag indians and their allies. For close quarters combat they used the ever-famous tomahawk, war clubs, and steel hunting knifes sold to them by French and British traders. During King Philip's War the Wampanaog fought to the death more often than not. Though civilian prisoners (often women and young girls) were taken to be ransomed later; any man or boy was almost always slain.

King Philips's War spread to the further reaches of northern New England and French North America when the Wabanaki Confederacy, partly inspired by Wampanoag rebellion in southern New England and with taciturn French support, natives attacked English forts and settlements in what is today Maine, New Hampshire, and Northeastern Canada throughout 1675-1677. Many of Maine's scattered settlements and homesteads were later laid to waste by the Abenaki in retaliation. Maine and New Hampshire residents organized militias and fortified their homesteads like their southern brethren had previously. In 1676 Wampanaoag warriors and their families fled to Cochecho, New Hampshire, near what is today Dover, to seek refuge with their cousins the Abenaki.

Shrewd local trader and militia major Richard Walderne (or Waldron) organized a mock battle between a band of 400 warriors, comprised of roughly half local Abenaki and the rest fugitive Wampanoag. The supposed friendly display of arms was actually a cleverly devised trap; Walderne's militia and two companies of Massachusetts troopers quickly descended on the warriors and arrested all of the Wampanoag but spared the Abenaki braves. Several known warriors or minor chieftains were taken to the Boston for execution and the rest sold into slavery. The Abenaki never forgot nor forgave Walderne and the settlers of Cocheco for this act of treachery. In 1689 Abenaki braves attacked Cocheco killing 23 and capturing 29 of the township's settlers. Walderne though in his 60's was among the first the die; tortured and mutilated by the Abenaki who had despised his unfair trading practices, gaining their revenge following the betrayal of Wampamnoag some thirteen years before.

Eventually agents acting on behalf of James the Duke of York, future King of England as James II, brought an end to conflict by 1677. They allegedly threatened the Wabankai peoples with Mohawk intervention if they did not cease their campaign.

Around 600-800 New England soldiers and militia were killed during King Philips' War. Close to 2,000 homes or properties were burnt or destroyed in addition to 300-500 English colonials who were killed, wounded, or otherwise displaced. At least 3,000- 4,000 indians if not more died during the conflict. Kyle F. Zelnor remarks, unequivocally, in A Rabble in Arms (NYU, 2009) that “King Philips' War was the most deadly and important conflict in the history of colonialNew England .”

Suggested Further Reading

Color etching depicting sachem Metacomet, the "King of Mount Hope", engraved by Paul Revere 1772

The son of sachem Massasoit, Metacomet was the paramount leader of the Wampanoag people who stretched throughout southern New England from Western Massachusetts into Connecticut, Rhode Island, and southern Massachusetts on the Atlantic Ocean. Metacomet ruled from Mount Hope Bay on the border of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Plymouth

Plymouth born Rhode Island officer Capt. Benjamin Church

Battle between colonial militia and Pequot Indians during the Pequot War, 1646-1648

New England tribal distributions during the time of King Philips War

Act I

Act I

King Philip’s War came about after further English colonial encroachment on tribal lands in New England. Another major factor was the belief that Metacomet’s brother, Wamsutta, had been killed perhaps by poison after meeting with colonial representatives in 1662. Sometime in the winter of 1675, one of Metacomet's interpreters John Sassamon went missing and was later found murdered. It was known by few among the colonials, Benjamin Church among them, that the Wampanoags and their allies were clandestinely preparing for total war with the English. Evidently when Sassamon learned of this he went to Massachusetts authorities to tell them of the news. By the time Sassamon's murderers were arrested and later executed, the tribal confederacy of Wampanoag and Nipmuck amongst others had already begun attacking settlements and killing colonial homesteaders from June-November 1675. Frequent raids were carried out throughout Massachusetts , Rhode Island , and Connecticut with several cities burned and put under siege as a result of the conflict. Captain Benjamin Church left his quiet coastal home at Little Compton, Rhode Island in June of 1675 with the area's militia to search for Metacomet and hostile native tribes throughout Rhode Island and parts of southern Massachusetts.

Attack on Church's company at Tiverton during the Battle of Peas Field 8 July 1675

The first major engagement of King Philip's War was fought at Fogland Point nearby the Almy's Peas Field, known colloquially as the Battle of Peas Field. Captain Benjamin Church and a company of 30 soldiers stumbled upon a large war party near the Fogland Point in what is today Tiverton, Rhode Island. They fought desperately against nearly 300 Indians for two hours, nearly overtaken several times until rescued by a vessel commanded by Captain Roger Goulding, only sustaining minor casualties in the heated attack on the beach. In early August of 1675 the town of Brookfield, Massachusetts was put under siege by Nipmuc natives led by the warriors Muttaump and Matoonas. Known also as Wheeler's Surprise or Wheeler's Ambush, the town was raided and then the Nipmuc attempted to burn the 75 inhabitants and a Massachusetts Bay platoon of 40 men led by Capt. Thomas Wheeler alive in the town's fortified manor house. For three days and two nights the Nipmuc continually attempted to immolate the blockhouse and/or drive the colonials from the safety of the manor. Wheeler's men killed half a dozen or more of the Nipmuc by the time Major Simon Willard and 48 Massachusetts Bay troopers came to their rescue and chased the Nipmuck band off.

On the first day of September, Nipmuck warriors attacked again in north-central Massachusetts, killing and scalping a man in Deerfield and then slaying eight more homesteaders fifteen miles north in Northfield. Three days later a mounted detachment of 36 Massachusetts cavalry led by Capt. Richard Beers was ambushed outside Northfield and massacred. Capt. Beers and four of his men made a last stand atop what later came to be known as Beers Mountain before they were killed by native musket balls. The slain Massachusetts troopers were beheaded by the Nipmuc warriors who had become drunk on pilfered rum. Several survivors of the doomed columns' supply train made it back to the settlement of Hadley to report the bloody massacre. Connecticut Major Robert Treat evacuated the Northfield settlers the next day. As his mounted column and the refugees of Northfield rode down the trail they most certainly despaired over the grotesque heads of their slain countrymen atop pikes lining the trail south.

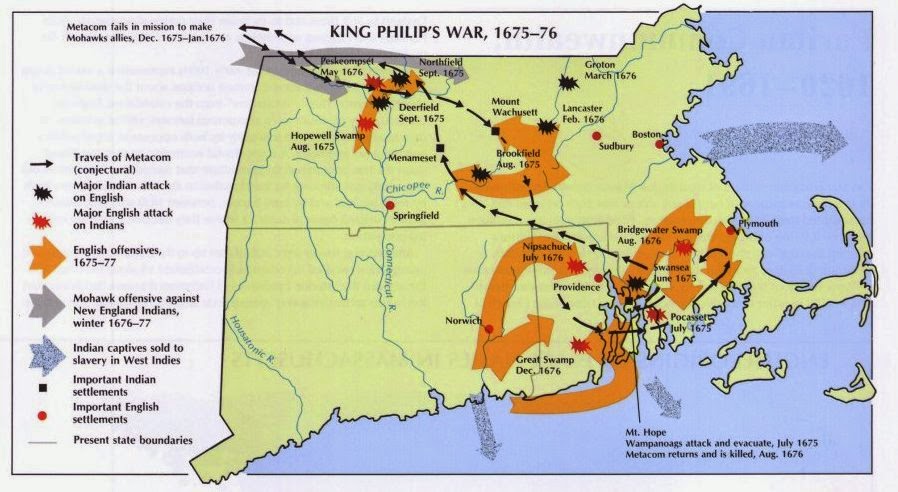

King Philips War Campaign Map, 1675-1676

Hadley to the south became a military garrison and headquarters as well as a safe haven for the wars' refugees. Northwestern Massachusetts remained under siege throughout the harvest threatening the food supply of the now swollen Hadley garrison. A Massachusetts Bay colony militia column of 80 men led by Capt. Thomas Lathrop was sent in late September to retrieve grain, corn, and wheat from the town of Deerfield's harvest. The militia set forth at a slow pace north in a long running wagon train, some men having placed their weapons in the carts meant to transport the grain back to Hadley. Forgetting even rudimentary lessons about how their native opponents liked to fight-no scouts rode ahead nor were pickets posted on their flanks, the Lathrop column was massacred in the ensuing rout. Some were filled with arrows or clubbed and then scalped following their retreat into the forest after the ambush. A small piddling stream running through a swampy area known as the Muddy Brook soon became choked with dead bodies, blood, and gore-hence, the Bloody Brook Ambush. Only five or so men lived to tell the tale of the massacre.

The Ambush at Bloody Brook, South Deerfield, Massachusetts, September 1675

In October, the Pocumtuc launched a brazen attack on their literal neighbors in Springfield when they poured out of their fort on Long Hill in what is today Springfield's south end neighborhood and burnt the town down. They killed two Massachusetts Bay colony officers before sacking the town and scattering its inhabitants. Many were wounded and thousands of dollars in property lost as a result of the Springfield attack. Dozens more would have been slain or taken captive had not Toto, known to history as Toto the Windsor Indian, ran nearly twenty miles from Windsor, Connecticut to Springfield in order to warm them of the impending attack. The burning of Springfield had been particularly shocking because the Pocumtuc people had been at peace with the settlers of Western Massachusetts and the Pioneer Valley for many years beforehand and had essentially no provocation to attack Springfield.

The tide of war turned in the colonists favor following the Great Swamp Fight (or Great Swamp Massacre) of over 300 Narragansett at their winter lodgings in December 1675. Governor of the Plymouth colony and General of the United New England militia Josiah Winslow (b.1628-1680), led the New England army of around 1000 Englishmen and another 150-200 allied natives in person along with a slew of officers from all the colonies. Their target was the winter redoubt of sachem Canonchet in what is today South Kingstown, Rhode Island.

Colonial militia attack a native fort during King Philips' War

The Great Swamp Fight, December 1675

Act II

The Great Swamp Fight was to be the largest battle of the conflict and the most significant colonial victory as well. Benjamin Church was given permission by Governor Winslow to reconnoiter the fight for the fort with a handful of men. His rangers killed several Wampanoag outliers before charging into the fort to take part in the prodigious slaughter now ensuing from within. Warriors and non-combatants were being cut down and shot. Some women and children likely burned alive in their wigwams as dozens of warriors fled the fort. The cost of the battle was staggering for both sides; no less than 400 Wampanaog were killed and at least half that number were captured and executed later. The New Englander's lost 70 killed and 150 wounded of which 50 or more later died from their wounds.

Raid on Lancaster 10 February 1676

Once bustling towns and productive frontier settlements fell under a shadow of war for well over a year as the brutal guerrilla war on the frontier played out. The native and colonial populations suffered dearly as a result in both Rhode Island and in Massachusetts. In February of 1676, the town of Lancaster, Massachusetts was raided and the Rowlandson's fortified house was burned to the ground. Twelve were killed and twenty-four taken captive by the Nipmucks, including Pastor Rowlandson's wife Mary (b.1637-1711) and several of their children who remained captives of the Wampanaog for more than four months thereafter. In late February, attacks and large movements of warriors were seen less than ten miles outside the city of Boston. Only weeks later, Metacomet's warriors attacked their furthest south in the war when they burned down the settlement of Simsbury on the Farmington River in Connecticut just fourteen miles northwest of the colonies capital at Hartford. Local legend maintains that Metacomet watched the burning of Simsbury and parts of what is now Farmington from atop what is now known today as Metacomet Ridge. Longmeadow, Marlborough, and Rehoboth in the Plymouth colony were all attacked in the same week with great loss of life and property. Led by the colonies aged patriarch Roger Williams (b.1603-1683), Providence was abandoned by its inhabitants and later burned down on 29 March by the Narragansett. The town of Warwick in Rhode Island

In April of 1676, the sachem of the Narragansett tribe, Canonchet, was captured by a group of Connecticut and Pequot Indians led by Capt. George Dennison in a raid of Narragansett tribal land in Eastern Connecticut. After he was ambushed Canochet attempted an escape into the forest but he was run down by a young Pequot warrior and then detained by the Connecticut militia. Taken in chains to Stonington, Connecticut, Canonchet was offered generous peace terms if he surrendered the Narragansett to colonial authorities and gave up the hiding place of his chief Metacomet. Canonchet replied to his Connecticut captors, "I will not surrender a Wampanoag nor the paring of a Wampanoag's nail." When the brave chieftain was told he'd be shot the following morning by the Pequot he replied, "It is Good-I shall die before my heart is soft, or I have said anything unworthy of Canonchet." After his execution his head was sent to Hartford where it was displayed publicly for several weeks.

Act III

Battles and massacres continued on however without the capture or death of the paramount leader of Wampanoag, Metacomet. On 20 April, 500 warriors came down from Mount Wachusett in Worcester county and attacked the important hub settlement of Sudbury. Upon hearing of the attack on Sudbury the captain of the Milton militia, Samuel Wadsworth, an experienced soldier by all accounts, took 50 Massachusetts Bay colony militia on a march from Marlborough to relieve Sudbury. As they neared the township a band of native New England warriors made themselves visible then quickly disappeared into woods. Wadsworth ordered his men in pursuit and right into the clutches of a rather obvious ambush. His men fought bravely from underneath the rocky cover at Green Hill until the native warriors set their defenses on fire forcing Wadsworth men's out into open where they were shot down to a man. Wadsworth and his second-in-command, Capt. Brocklebank, were later found with thirty or so of their militiamen; all had been scalped, stripped, and left to rot atop Green Hill.

In late June, Connecticut Major Talcott with 250 mounted troopers and 200 Pequots launched a punitive expedition towards Providence, burning Narragansett settlements and killing or capturing 238 on the Connecticut-Rhode Island border, many in the former category. Capt. Church's rangers took to the forests outside Middlebourough in mid July, scouring the peninsula for traces of the elusive King Philip. This was an area that Church knew well. On 1 August, a large band of natives was spotted outside Bridgewater in the Plymouth colony. Church's rangers and some Bridgewater militiamen gave chase and soon routed the Wampanaog near Monponsett Pond. Capt. Church was nearly killed in the skirmish before his men overtook and killed or scattered this mysterious rogue Wampanoag band. Among the few who escaped this raid was sachem Metacomet who fled with nothing but his rifle and the clothes on his back. His wife and son were left behind and captured by Church's men. Following the skirmish one of Metacomet's captured braves when questioned by Church told him frankly, "You have now made Philip ready to die. For you have made him as poor and miserable as he used to make the English. You have killed or taken all his relatives. You will soon have his head, for you have broken his heart."

In late June, Connecticut Major Talcott with 250 mounted troopers and 200 Pequots launched a punitive expedition towards Providence, burning Narragansett settlements and killing or capturing 238 on the Connecticut-Rhode Island border, many in the former category. Capt. Church's rangers took to the forests outside Middlebourough in mid July, scouring the peninsula for traces of the elusive King Philip. This was an area that Church knew well. On 1 August, a large band of natives was spotted outside Bridgewater in the Plymouth colony. Church's rangers and some Bridgewater militiamen gave chase and soon routed the Wampanaog near Monponsett Pond. Capt. Church was nearly killed in the skirmish before his men overtook and killed or scattered this mysterious rogue Wampanoag band. Among the few who escaped this raid was sachem Metacomet who fled with nothing but his rifle and the clothes on his back. His wife and son were left behind and captured by Church's men. Following the skirmish one of Metacomet's captured braves when questioned by Church told him frankly, "You have now made Philip ready to die. For you have made him as poor and miserable as he used to make the English. You have killed or taken all his relatives. You will soon have his head, for you have broken his heart."

Assassination of King Philip outside Mount Hope August 1676

The regal chieftain's skull was placed on a pike in Plymouth where for over twenty years it stood until it turned bleached and began to crack. Alderman supposedly took one of the revered sachems hands as a war trophy; later preserving it in rum, he made a small amount of coin the rest of his life showing it to curiosity seekers at taverns and barrooms throughout the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies. Despite Metacomet's death the war would continue on until the final pitched battle was fought at Turner's Falls outside Springfield in May of 1676. In this battle the last remnants of Nipmuck warriors were finally defeated and driven from the northern reaches of the colony. In June the last organized band of Wampanaog natives was defeated and killed or captured outside of Marlborough, Massachusetts and thus King Philips' War came to an end.

Opposing Forces: Colonial Militia and Native Warfare, 1637-1675

New England's militias were the only military force in the colonies since England had no standing army in American at this time. Male colonists were required by law to remain armed, supplied, and ready to muster out with their units whenever called upon, though one could buy one’s way out (few did) or could give a younger son or two, permission to join, as was customary at the time. In fact very few volunteered especially early on in the conflict; many had to be pressed into service with the threat of fines or jail time creating a rag-tag, poorly trained and disciplined force led by inept officers who had been appointed because of political and social connections. Following the Bloody Brook Massacre in September of 1675, New England Confederation commissioners proscribed added quotas of 158 men for Plymouth, 315 for Connecticut, and 527 for Massachusetts Bay. In theory, New England had an "English" army of well over 1000 soldiers plus an additional 500-750 friendly Indian allies amongst the Pequot, Mohegan, Tunxis, and Sakonnet tribes.

"First Muster of Massachusetts Bay Militia in Salem 1637" by Don Troiani

For many militia captains it was agonizingly laborious to get these men to march quickly, to get into battle formation, and to attack or retreat as a unit with a modicum of discipline and order. Armaments and weaponry were fairly standardized across most of the New England army. Smoothbore matchlock muskets were used by the average militia soldier. These were heavy and cumbersome .75 caliber "shoulder breakers" which were horribly inaccurate even at close ranges and which took nearly a minute to reload. Swords were commonly in use by the gentry and cavalry troopers. Pikes were also popular throughout the New England militia system during this period.

The native tribes of New England fought similarly across the frontier theaters of King Philips' War. The element of surprise was always paramount. The ambuscade and raid were prized above all methods of warfare though Metacomet's warriors fighting in large numbers were also highly effective against the untrained rabbles of New England militia. Long and short spears were used for medium ranged combat while bows and arrows and an increasing number of muskets were also used at long range by the Wampanoag indians and their allies. For close quarters combat they used the ever-famous tomahawk, war clubs, and steel hunting knifes sold to them by French and British traders. During King Philip's War the Wampanaog fought to the death more often than not. Though civilian prisoners (often women and young girls) were taken to be ransomed later; any man or boy was almost always slain.

King Philips' War in Northern New England, 1676-1689

Shrewd local trader and militia major Richard Walderne (or Waldron) organized a mock battle between a band of 400 warriors, comprised of roughly half local Abenaki and the rest fugitive Wampanoag. The supposed friendly display of arms was actually a cleverly devised trap; Walderne's militia and two companies of Massachusetts troopers quickly descended on the warriors and arrested all of the Wampanoag but spared the Abenaki braves. Several known warriors or minor chieftains were taken to the Boston for execution and the rest sold into slavery. The Abenaki never forgot nor forgave Walderne and the settlers of Cocheco for this act of treachery. In 1689 Abenaki braves attacked Cocheco killing 23 and capturing 29 of the township's settlers. Walderne though in his 60's was among the first the die; tortured and mutilated by the Abenaki who had despised his unfair trading practices, gaining their revenge following the betrayal of Wampamnoag some thirteen years before.

'Major Waldrons Terrible Fight'-19th century depiction of Walderne's death

Eventually agents acting on behalf of James the Duke of York, future King of England as James II, brought an end to conflict by 1677. They allegedly threatened the Wabankai peoples with Mohawk intervention if they did not cease their campaign.

Conclusion

Around 600-800 New England soldiers and militia were killed during King Philips' War. Close to 2,000 homes or properties were burnt or destroyed in addition to 300-500 English colonials who were killed, wounded, or otherwise displaced. At least 3,000- 4,000 indians if not more died during the conflict. Kyle F. Zelnor remarks, unequivocally, in A Rabble in Arms (NYU, 2009) that “King Philips' War was the most deadly and important conflict in the history of colonial

Many thousands of New England's native peoples, both enemy combatants, loyalists, and Praying Indians, had been systematically slaughtered, imprisoned, enslaved, relocated, or exiled following King Philips' War. After the conflict had concluded, enslaved Wampanoags and Narragansetts were sent by the hundreds from New England to the Caribbean and West Indies including King Philip's wife and young son. Today the legacy of the colonial wars against the New England Native American peoples is both a deeply shameful but an important episode of the collective history of New England .

A Rabble in Arms: Massachusetts Towns and Militiamen During King Philip's War Kyle F. Zelnor (NYU, 2009)

Flintlock and Tomahawk: New England in King Philips' War D.E. Leach (1958-2009)

Flames over New England: The Story of King Philip's War 1675-1676 By Olga Hall-Quest (Dutton, NY, 1969)

Flintlock and Tomahawk: New England in King Philips' War D.E. Leach (1958-2009)

Comments

Post a Comment