Guerrilla War for Algeria: Revolution, counter-insurgency, and the French way of war, 1956-1961

Algeria’s War for Independence, fought from 1954-1962 is one of the most important conflicts fought in the post-War era, arguably the premier example of neo-colonialism, & the implementation of insurgency and anti-insurgency tactics in the modern age.

France ’s initial conquests of Algeria began with their invasion the coastal regions in 1830, ending with an outright defeat of the Ottoman Empire for control of coastal Algeria in 1848. With their conquest half complete France was drawn into conflict with the sultanate of Morocco , eventually confirming de facto control over Algeria with the Treaty of Tangiers 1844.

Algeria ’s revolution militarily speaking was built on the tenets of the Maoist guerilla war and the irregular war. The insurgency portion was fought in both urban and rural environments throughout the conflict, never truly metabolizing into a conventional conflict. For the FLN it was bloody and tough challenge, overcome through France ’s inability to wage total war for the possession of Algeria , and the ruthless and at first seemingly ineffective campaign of revolutionary terror & guerrilla war waged by the FLN, and the other supporters of the Algerian independence movement.

Battle of Algiers

French Paras in Algeria during the Algerian War

Since the invasion of Iraq and the corresponding insurgency of 2003-2011, renewed interest in the military campaigns of the Algerian War from the United States and Western European spheres of military education has made the conflict a precursor study in the greater study of guerrilla/insurgency tactics in the modern age.

Prelude, French Algeria

Colonial expansion began in earnest though colonization greatly bolstered the Algerian infrastructure and population into the 1900’s. By 1914, France ’s presence in West Africa was domineering to say the least, controlling a sizable portion of the Western continent by the start of World War I. Adding possession of Madagascar , leases on Chinese ports, Cochinchina (Vietnam ) and control of Cambodia amongst many others, France dominates the imperial scene of the 19th and early 20thcenturies like no other nation next to the Britain. After World War I, Metropolitan France governed between 60-70 million people from the Pacific to the Mediterranean through to the Red River on the border with Vietnam and China . Algeria always played an important role economically and culturally for France and for many French people as well. Algiers and French Algeria were both a colonial outposts and a stronghold for the French Foreign Legion. Indeed from the invasion of Algeria in 1830 until 1962, Algeria and its capital Algiers were important assets to France and its overstretched military, dependent on the (if somewhat exaggerated) masculine fighting prowess of the Foreign Legion and the much less respected or admired Colonial infantry to hold it.

The power of the colons or pieds noir, French citizens of Alsatian, Italian and Metropolitan birth who first came in any significant numbers following the collapse of the French Empire in 1870-1871, is also very important to the underlying socio-cultural hegemony (order) established in the years of colonization finally broken after World War II during the decolonization and the overall movement to liquidate imperial power globally from 1946 to circa 1982.

Guerrilla Revolution 1955-1957

The War for Algeria began in the bled, the wide reaching countryside, mountainous expanses, and rocky landscapes of southern Algeria where the majority of French, Algeria guerilla fighters, and loyal Muslim troops lost their lives in the brutal struggle to keep Algeria apart of France.

As it played out the Algeria Revolution became a Civil War as much as it was a war of insurgency, the French fighting to crush the rebellion at any cost, loosing both the military campaign and the campaign for the “hearts & minds” of Algerians in the major population centers and the ‘back country’, where the Algeria guerillas, (terrorists to the French and the colons) of the National Liberation Front (FLN) or Fellaghas ‘bandits’, drew their support from.

FLN waliya commanders, Belkacem Krim (left) and Ait Hamouda Amirouche (right)

The War in the bled centered around French outposts manned by some experienced Legionnaires and regular army men some of whom had fought in World War II in either the resistance or in the Free French Forces abroad. Others were veterans of the Indochina War and its penultimate battle at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. Many more conscripts who had left school, jobs, and their families to fight to keep Algeria French.

Their adversaries fighting for an independent Algeria drew their inspiration and support from their faith, local custom & history, and their experiences fighting for France from the Franco-Prussian War through both World War’s and in Indochina as well. Algerian’s no matter their services rendered or individual merit were always second-class citizens in their own country, never Frenchmen in practice or law. Typically the older generations who had fought in both World Wars for France remained loyal, called the Beni Oui-Oui, the Yes Yes [men], tens of thousands of Algerians would die by their own country men’s hands from 1955-1962 because of their loyalties, or lack thereof, to either side.

Throughout the conflict the FLN forces fighting the French especially those in the bled, known also as the Frontier, relied on the use of the somewhat antique weapons left behind by the American, British, Italian, and German armies during the North Africa campaigns of 1940-1943. The rest of their weapons were stolen from French convoys and outposts, taken off dead French soldiers or heirloom shotguns and hunting rifles, unsuited for a true guerrilla campaign. Many more were the weapons of farmers and hunters, shotguns and small caliber rifles.

FLN insurgent armed with an Italian rifle of World War II vintage

Conflict in the Frontier region would define the conflict and would not end until the complete withdrawal of France with Algeria ’s independence in July 1962. From 1955-1961, the ‘sector troops’ young conscripts with minimal training, led by equally inexperienced officers tried to pacify and defend the Algerian countryside for the fellaghas.

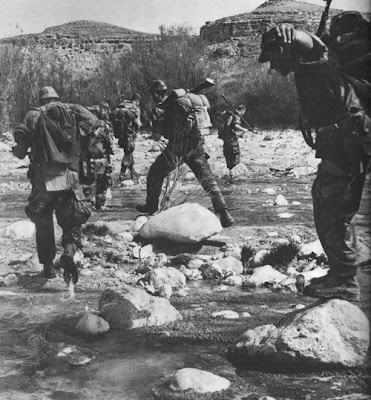

French soldiers on the march in an unknown sector, on the lookout for insurgents

While they fought the static war, ingloriously, it was French Foreign Legion and the Paratroopers who engaged in the non-conventional ground missions and airborne operations, primarily aimed at destroying the FLN’s military capabilities and capturing or killing its leaders in a bounty type system. From the French perspective body count was seen as the main objective, similar to the muddled objectives faced by the French and later the Americans in Vietnam.

Combat between the French authorities (police, regular army, and Special Forces) and Algerian revolutionaries had begun as early as 1955-1956. Bloodshed had begun sporadically, intensfying under the civil violence caused by the escalation of the conflict from a rebellion or ‘police action’, to a full-intensity conflict. The Battle for Algiers like the war in the Frontier was a guerrilla war of hit-and-run tactics, lightning raids, and seek & destroy missions. Severe interrogation techniques & torture were common, and the execution of prisoners used by both sides, assassinations/disappearances all too common in the Casbah and in the bled.

The Battle for Algiers itself began at a time when France was granting independence to both Tunisia and Morocco , while reeling from its invasion of Egypt, allied with Britain and Israel to prevent the Egyptians from nationalizing the Suez Canal , ending with a disastrous military effort and diplomatic outcome in October-November 1956. At the same time Paris was preparing to fortify the capital of French Algeria, Algiers , to protect French infrastructure and the colons & pied noirs (European) very way of life in their ancestral oasis home city. If Algiers’s had been a city divided for centuries leading up to the battle, when the bombs and gunfire of the FLN and French Paratroopers exploded in the city streets beginning late in 1956, Algiers would become a modern urban battleground, where martial law, and essentially a Police State were established by the French army Para commander, General Jacques Massu (b.1908-2002) and his 10e Parachute Division.

General Massu reviews his Paras', Algeria 1957

When the first bombs exploded in Algiers the shock and outrage in both the colon sector of Algiers and in Paris was pronounced, the Europeans in Algiers fearing for their life daily until their exodus at the end of the conflict. Using assassins and local girls dressed not in Algerian garb but “Western” & “European” clothing, the FLN targeted cafés, bars, and other European gathering spots for random bombings and shootings, creating a tense situation of urban guerrilla warfare, kept in check by an almost unrestricted but still limited counter-insurgency campaign.

The Battle for Algiers was decided less by bombs, small arms fire, and the air superiority of the French (the latter two useless for them during the actual Battle for Algiers), and more through intelligence gathering. Algiers was pacified through covert operations, the informant system, and most controversially, through the torture of suspected and/or captured Algerian freedom fighters. Throughout the battle and then the rest of the conflict certainly hundreds if not thousands of Algerians were tortured through various means (including electro-shock and brutal beatings) by the intelligence agencies of the French army. During the Battle of Algiers many of interrogators operating under General Massu’s 10e Divisional command were led by General Paul Aussaresses (b.1918). Click here for a clip of the retired Aussaressess discussing the use of torture during the Algerian War which aired on 60 minutes a few years ago.

By the end of the struggle for the Casbah and the greater city of Algiers, thousands were dead, mostly native Algerians but hundreds of French military, police, and colons were killed, grievously injured or otherwise assaulted during the close to year long struggle for the city. Hundreds disappeared, the targets of the French’s intelligence system and the assassination squads of the French army and the FLN. Some of these disappeared may have been killed through the sinister practice of death flights, a covert (black ops) means of disposing of insurgents and potential enemies discreetly by dropping them into the sea at nighttime from a helicopter.

Les Paras, French Paratrooper command 1956-1961

What can be termed a war within a war, the French Paratrooper command, the Paras’, operated as unquestionably the most effective, and then potentially harmful tool in France ’s arsenal during the Algeria War. Then and now they are the most complex to study as they are the certainly the most controversial aspect of the French effort in Algeria, due to their heavy handed tactics and their use of torture during the Battle of Algiers and the Battle of the Frontier during the climatic end to the guerrilla conflict. Para officers also participated in the attempted putsch in 1961 to overthrow President de Gaulle.

If over generalization can be permitted, the French used Paratroopers in two types of basic roles throughout the conflict, the most common being air-dropped in company sized squads as mobile-rapid deployment-intervention forces, perfect for reinforcing and rescuing ambushed patrols in the bled.

In this role the French Paras often engaged the enemy in classic seek & destroy missions, particularly useful in intercepting supplies from Tunisia and Morocco (in some cases weapons supplied by Egypt ). Able to strike at a moments notice through the use of handheld radios, supplied by the Americans, and the use of French Air force reconnaissance aircraft and later American, Sikorksy made helicopters, French paratroopers and para-Legionnaires were the “cutting edge of French military effort in Algeria” according to author Jean Mabire, a veteran of the Commandos de Chasse, in the book The Commandos (1988).

French soldiers depart from a helicopter into the bled during the conflict

These operations managed to kill and capture many leading FLN commanders; furthering the impressive record of the French Para service, which began heroically but ultimately tragically at Dien Bien Phu . The ‘hunting or hunter’ mentality was critical to the tactics of the French Para’s and the Legionnaires to some extent, who were trained and sent into the field of operations with the mission to drop, secure the area, and move objectively on to the target or targets in the field, neutralizing them through any means necessary. The basic problem in combating the FLN however was that neither the officers in command in the field nor the generals in the high command in Algiers took the time to study, recon, or gather meaningful intelligence outside of Algiers and the Casbah, in the bled and the Frontier where the guerrilla war was fought and where it was ultimately won. These sectors of the rural regions to the South and West remained militarized with the FLN unopposed in much of the vast territories to West towards Morocco and Tunisia respectively.

An H-34 helicopter drops Legionnaires in the bled

Paratroopers in Algiers and in the Frontier often targeted inadvertently or at times purposefully civilian locations (villages, settlements, and markets) in their quest to eradicate FLN resistance, brutalizing and ultimately alienating the rural populace, who in many cases were often pro-French or neutral at the very least. This played into the strengths of the guerilla-insurgent campaign, signaling the weakening of French authority throughout the country into 1959-1961.

Helicopters were critical to the Para’s campaigns in the Algerian frontier, not surprisingly the most unique and progressive technology of its time they were used to great success French paratroopers and piloted by Air Force pilots during the Frontier operations of 1957-1960. Helicopter raids were used effectively most notably during the 1959-1960 offensives of General Maurice Challe-whose Commandos de Chasse killed and captured many fellaghas during the end of the conflict with little loss of life on their side.

Zouave regiment of the Commandos de Chasse, 1959

Two other components were essential to the Para ’s success before, during, and after their service in the Algerian War. The first was very simply: the weapons, tactics, and training of the Paras during the period was top notch. Since they were the ‘crack units’ of French service there was a selection process and more refined training at the barracks and company level where unit comradery and cohesiveness were primary concerns. Training was done both in France and in North Africa. Both the Paras and Legionnaires received the best weapons during the Algerian Revolution. The reliable rapid fire MAT-49 submachine gun was the primary firearm of choice and was standard issue. Meanwhile the American made 1911 sidearm was a close second and favorite to non-com officers and conscripts alike. American made combat knifes, German World War II surplus, American radio equipment, and plenty of anti-personnel grenades (a favorite of Col. Bigeard) were also employed.

The second component which allowed for success was the excellent physical shape (aerobic endurance and physical strength), Esprit de corps, & tactical élan demanded from all who served in the Les Para fraternité (brotherhood). In combat or behind at headquarters many French Para commanders exemplified these characteristics. Officers like Colonel Marcel “Bruno” Bigeard (b.1916-2010) and Colonel Roger Trinquier, both members of 3e RPC, a colonial parachute regiment attached to General Massu’s infamous 10th Parachute Division, which occupied the Casbah during the Battle of Algiers, are two famous examples.

A veteran of World War II, Bigeard had fought in North Africa, the liberation of France, and later commanded men who dropped on Dien Bien Phu in 1954 for support, was the quintessential French Para of the post-War period. Obsessed with physical fitness and battlefield command Bigeard never went into combat armed. As an officer and Para Colonel he preferered only his maps, a radio, and binoculars to survey the battleground around him. Bigeard was a man who loved combat, marching on campaign, and the tactics and strategies behind beating the enemy no matter who held the advantage.

He had a nearly legendary ability to avoid wounds and death in combat save for two wounds suffered in Algeria, the first suffered in the bled when he was shot in the chest in 1956, just two years after surviving the hellish death march and imprisonment of the Viet Minh following the defeat at the Siege of Dien Bien Phu. Two months later while recovering on a jog through Algiers alone and unarmed, a young Algerian shot him in the back. Bigeard chased the frightened boy away and survived by jogging back to the his barracks.

He had a nearly legendary ability to avoid wounds and death in combat save for two wounds suffered in Algeria, the first suffered in the bled when he was shot in the chest in 1956, just two years after surviving the hellish death march and imprisonment of the Viet Minh following the defeat at the Siege of Dien Bien Phu. Two months later while recovering on a jog through Algiers alone and unarmed, a young Algerian shot him in the back. Bigeard chased the frightened boy away and survived by jogging back to the his barracks.

The Battlefield Commander, Marcel 'Bruno' Bigeard

Trinquier was a veritable expert on Southeast Asia , China , and Indochina having fought the Viet Minh in irregular operations from 1946-1954. He later served with distinction in Algeria as well replacing Bigeard as commander of 3e and commanding for a time during the Challe Offensive in 1959.

His book Modern Warfare, A French View of Counter-Insurgency, first published in the year 1961 is standard reading for modern military officers, infantrymen, and Para-commandos today. This reading is supposedly still influential amongst many American officers who served, studied, or analyzed the Vietnam War, the Cold War conflicts in Africa, and the recent insurgencies inIraq , Afghanistan , and the insurgency waged currently by Islamic fundamentalists in Northern Mali .

His book Modern Warfare, A French View of Counter-Insurgency, first published in the year 1961 is standard reading for modern military officers, infantrymen, and Para-commandos today. This reading is supposedly still influential amongst many American officers who served, studied, or analyzed the Vietnam War, the Cold War conflicts in Africa, and the recent insurgencies in

Modern Warrior, Colonel Trinquier

End to conflict, Algerian Independence

French Algeria came to an end during the socio-political upheavals of 1961-1962 which almost brought the government of France crashing down into total civil anarchy. The most hard-line officers who became gangsters and terrorists themselves, sensing the collapse of French Algeria, formed the loosely associated Organisation de l'armée secrete, or OAS. A clandestine para-military and political front, targeting deserters, political enemies, and President Charles de Gaulle (b.1890-1970) himself. OAS activity was preceded by the attempted putsch of a number of French generals including Challe and General Raoul Salan (b.1899-1984) in Algiers, April of 1961.

Eventually, President de Gaulle, originally unwavering in his support for a French Algeria, finally relented, sensing a political & diplomatic catastrophe, “betrayed” France by giving Algeria its independence in 1962.

Recommended Further Reading

The Algerian War 1954-1962 by Martin Windrow, illustrated by Mike Chappell (Osprey Publishing)

My Battle of Algiers, a memoir by Ted Morgan (Smithsonian Books, 2005)

A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962, by Sir Alistair A. Horne (New York, 2006)

Also, the fictional portrayals in the films The Battle of Algiers (1966) & Intimate Enemies (2007)

Comments

Post a Comment